Do we have a choice about the subject of our creative work? In a recent interview with Francesca Steele of Write-Off podcast, Tessa Hadley said, “There is no choice about what you write…an interesting discovery…no, it isn’t a choice, you just have to find the thing that is yours.” They were discussing the writing of domestic fiction, of which Tessa Hadley is considered a modern master. For some thoughts about domestic fiction as a genre, read this reflection by Soledad Fox Maura at Lit Hub. Also, must mention Tessa Hadley’s stunner of a short story in a recent (July 24, 2023) The New Yorker. You can listen to her read it here too, “The Maths Tutor”.

A few years ago, I would have disagreed with Tessa Hadley, believing that of course a writer could choose their subject. But now, after years and drafts attempting to write something with Meaning (capital M) about Big Important Issues (climate change, poverty, the impacts of war, attachment theory, to name a few), I do agree with her.

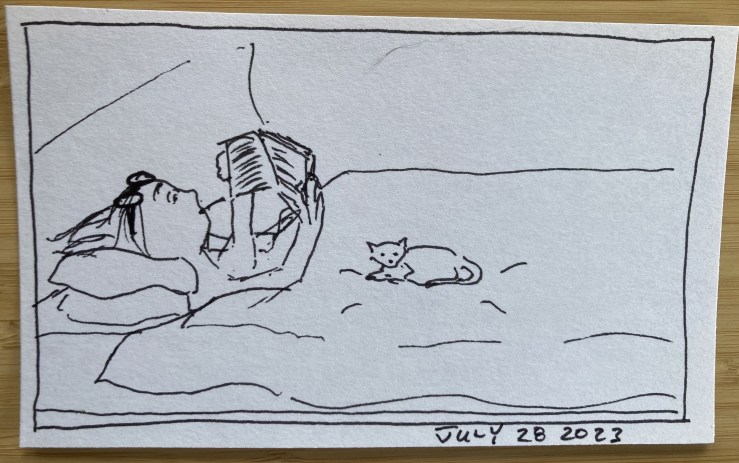

It doesn’t matter what I try to write, the stories of my family—growing up, as well as my experiences in a long-term relationship and raising my own children—bubble to the surface. I’ve wasted a lot of time and energy resisting this writing, or at least trying to hide it behind a Big Meaning facade. But I’m starting to make peace with the themes my writing presents: raising kids, marriage, cooking, being raised by parents with mental illness and addictions. It is who I am, how I have become the person I am, and, importantly, provided my foundation and lenses for my viewing of the world. It’s this inner voice—unique for every person—that readers will connect to if I can get it to the page. I’m only beginning to trust my own voice (that it’s good enough).

Coupled with this challenge is another: when I choose to centre my family life in my creative writing, the refrain from trusted readers is often that it’s too much all at once (I’m paraphrasing, but this is the gist of it). One dear friend explained reading my stories or poems feels almost like an assault to her senses. She really means this kindly, and I accept it that way too, but I’ve struggled to understand what I might do differently. There’s so much strangled emotion waiting and wanting to spring out. I don’t know how to tell these stories in a way a reader might absorb them with any pleasure or entertainment at a pace that engenders empathy as opposed to shock, or worse, pity.

The last few months of writing flash pieces, narratives that follow a “story arc” but are less than 1000 words, have been generative and instructive. Flash, as a form, focuses an emotional moment. There isn’t room for much else. In some of the pieces I’ve generated—over 26 unique story drafts since the beginning of May (woohoo!)—I’ve practiced approaching some of my family stories using different perspectives, angles, and styles. I’ve discovered the flash form might be a method for me to “break up” the emotions and the moments in a way that is softer on readers, easier to digest, provide some white space and pause for breath. That way, several flash pieces assembled could become a kaleidoscope (of different focal points, different angles, etc.) of “what happened”, layering texture and meaning by using not just simply concentrated content, but a strategic sequencing too. An arrangement where the spaces in between could provide much-needed rests and pauses for recovery. A working theory anyway, I’m now trying.