In the past, a shift in how I viewed the world happened quite literally. I travelled to New Zealand over twenty-five years ago and discovered a large world map with New Zealand at its centre. Up until that point, my education and experiences about what the earth looked like and where the continents were located in relation to one another was depicted with two views (remember, this is before Google maps). The first was on a globe whose axis tilted away from my body and fastened to a stand. The attached points of axis bisected the north and southern poles, focusing spinning attention to the northern hemisphere (Europe, Russia (USSR), North America, half the world’s oceans). If I had to find New Zealand, the country where my mother was born, I needed to bend upside down to see it.

The other world view was a flat, two-dimensional map, the sort that gets tacked up on bedroom walls or ceremonially unrolled to obscure the chalkboard at the front of classrooms. On these maps the Americas (North and South) are rendered on the left-hand side and Europe, Africa, Russia, Asia, Australia (and New Zealand) on the right-hand side. The Pacific Ocean is split (so one doesn’t quite appreciate how vast it is) and the Atlantic Ocean takes over the middle ground.

On the map I discovered in New Zealand so many years ago, the two tiny islands commanded the middle space and suddenly I appreciated how far away the country really is from most of the other continents, floating there in a large blue pool (the Pacific Ocean). In the NZ maps I was stunned to discover how close Russia and Alaska are to each other (the western tip of Cape Prince of Wales in Alaska is 88.5 kilometers (55 miles) from the Southern point of Cape Dezhnev in Russia – if I were driving this distance across the Bering Strait, it would take me less than an hour!). And with this realization my mind moved through a reshuffling of Cold War history and Canada’s shared responsibility with the US for continental air defense through NORAD (North American Air Defense Command).

Of course, with Google maps available at our fingertips these days, my naive view of geography and related epiphany is outdated. My point is that I had accepted these two views of the world “presented” to me without questioning the perspective (and possible motives) of their presentations. I’ll get back to this thought shortly.

Another map and another example. This time focusing on the north-east region of North America (Ontario, Quebec, the Atlantic provinces, the states along the eastern seaboard, the southern shores of the great lakes, lining the Mississippi River and other confluences and tributaries – the water here is important). This map, a map free of border lines (province, state, or country), depicted the diversity of Indigenous languages with coloured circles of concentration. Sometimes the colours overlapped, indicating mixed languages in regions, but on that map (a simplified version from the picture below), it was instantly clear how Indigenous languages mirrored waterways (water being an essential human resource). Again, I experienced a mind-bending reshuffling to appreciate how cultures depend and thrive in relation to land and water. But also, how superficial country (province and state) borders are. Crayon lines drawn by Kings and Queens, heads of state. Crayon lines our loved ones fight for and die on. Crayon lines that shift and move, depending on which resource they’re circling, gold, uranium, olive groves, copper, waterfalls, coal, legislation, policy, justice, freedom, the list goes on.

What does this have to do with creative writing practice? Well, a lot actually. It’s a bit of a conceptual leap, yes, but bear with me. The way we carve categories in the world around us, be they continents, countries, or the way we name the world with words, impacts the way we “see” the world, how our perceptions are influenced. Words matter – they determine how we think.

These quotes from a recently published piece by Christine Kenneally in the

Scientific American November 2023 Issue:

“Culture shapes language because what matters to a culture often becomes embedded in its language, sometimes as words and sometimes codified in its grammar. Yet it is also true that in varying ways a language may shape the attention and thoughts of its speakers. Language and culture form a feedback loop, or rather they form many, many feedback loops.”

“…the more we ask empirical questions about language and its many loops in all the world’s languages, the more we will know about the diverse ways there are to think like a human.”

I need to reread David Abram’s astounding book The Spell of the Sensuous which explores similar ideas, comparing Western language development to Indigenous ones. A review of the book written by Émile H. Wayne offers this distillation:

“When our ways of thinking and knowing are rooted in the actual soil of our actual communities…we are called out into the world where we meet, in every bodily sense, the consequences of our own actions. Non-human nature becomes present, aware, vocal, integral to our being. We find ourselves living not in the midst of our abstractions – nation-states, linguistic group, political party – but as members of a living, breathing, often suffering, body of relations.”

For these reasons (and others – this post is too long already), I have started to learn Anishinaabemowin with the Kingston Indigenous Language Nest. I would like to better understand how Indigenous Peoples of the land on which I learn and live name and view the world. I want to expand my worldview.

I would be remiss if I failed to name an additional world view shift I am making. This month, I made the very difficult but courageous decision to leave my marriage. Quite simply, I want to be independent. This is the language I have been using. I do not feel I am leaving my husband…we are bound to one another through our children and the life we have created together, both in the past and the one we create in the future. Our relationship shifts – it is my hope we remain friends who love each other. It is a painful separation. I am blessed to be surrounded by people who love and hold me, keep me floating. Writing my way through is helping. Also art. And songs. And lifting the Dahlias from the soil to overwinter. I’m not sure what garden they will be planted in next year, but they are waiting in the dark. Kind of like me.

I have been learning names of animals in the Anishinaabemowin classes I began. We learn as children do, with songs and games. It’s fun. The other night, I discovered a gray tree frog in my kitchen. It’s the first time in close to twenty years of living in this house that I have found a frog within. Agoozimakakii is the Ojibway (a dialect of Anishinaabemowin) word for tree frog. Phonetically it is pronounced: ah-goh-say-mah-kah-ki. Today I am leaving this house, this home…when I looked up the spiritual meaning of finding a tree frog in one’s house, I discover it’s “a symbol of transformation…In some Native American traditions, the frog is seen as a guide who can help individuals transition between different stages of life.”

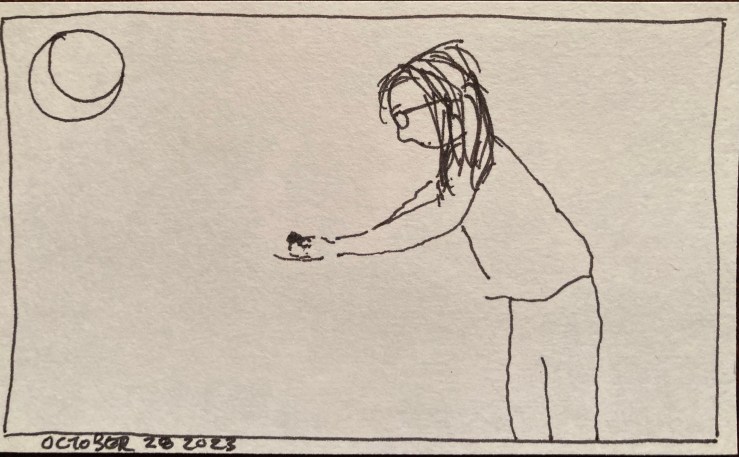

I had a hard time catching the poor wee thing, the heart shaped tree frog slightly smaller than the palm of my hand. She was fast and strong, and she hopped from my hands several times, landing with splats on the linoleum. Finally, I cupped her in my palms and placed her back outside under our exquisite moon, its light making our skins glow.

I have opened the borders of my soul with these moves, these shifts, expanding my view of the world with new perspectives. I aim for Mino Bimaadiziwin, an Anishinaabemowin phrase meaning “to live the good life” in a wholistic sense – “the intelligence of the mind is inspired and informed from the intelligence of the heart.” It is terrifying, but also, feels exactly right.

Be brave – Aakode’ewin. In the Anishinaabe language, this word literally means “state of having a fearless heart.” So, this is how I step into this new-to-me kaleidoscopic landscape and learn to name the world.