Sometimes I must be dropped in the Marshall Islands to realise I’m in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. It often takes me a long time to see things.

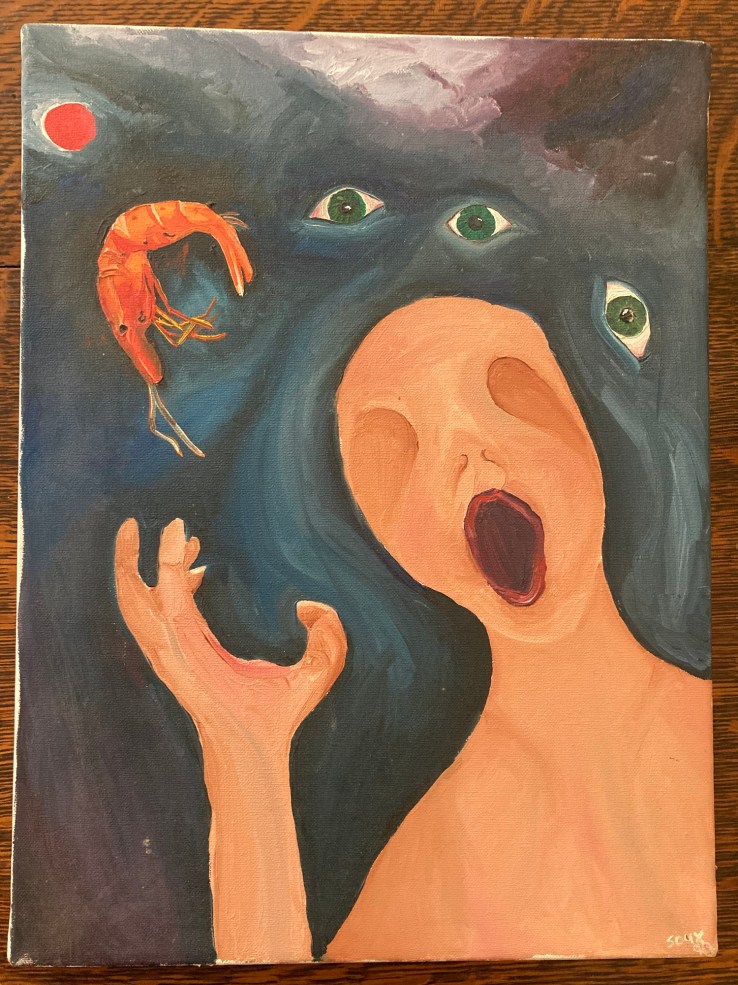

I went through a phase in my late teens and early twenties painting figures with no eyes – the two pieces here date from that era. Most of the artworks I produce are given away as gifts[1]. I can’t imagine many recipients of these screaming figures with their eyeballs floating in space might still grace their walls with my works. These two pieces might be the only ones left. They hang on the walls beside my writing desk.

I know they look scary. They aren’t meant to be. My high school art teacher disliked them. At the time of their creation, they didn’t reflect a mood I was in (I was quite happy and content, not dark or brooding). At the time of creation, I simply followed where my paintbrush or my pencils took me, delighting in the creaminess of oil paints, their tree-sap scent, and the ease with which pencil marks shadow contrasts between light and dark. Perhaps it was a way to work through an earlier terror, I don’t know. I never had an explanation for why I painted these subjects, I just did.

Decades later, hanging on new walls in a new space, staring at these works above my desk, they spark curiosity. And reflection. Looking back upon the intervening years of marriage and raising[2] a family, I can’t help but interpret their imagery as an almost wilful blindness. A warning for what it would take for me to manage my life choices diverting my path from art.

More context. I was flattened after completing my undergrad. In those days, the degree required a written thesis, complete with ethics review submission, primary data (raw) collection, analysis, interpretation and synthesis. Mine explored how child development influences a child’s ability to draw emotions. I went into three different schools and multiple classrooms of kindergarten to grade three students and collected their drawings of “a person who is ‘sad’, ‘angry’ and ‘happy’”. My supervisor, a new to the department prof, studied the tools with which child welfare court cases might be helping or hindering child testimonies. I won’t get into the Pandora’s Box of issues this research illuminates with our justice system and the rights of children. My thesis work was a departure from the neurophysiology and neurochemistry I’d focused on through the science degree, deliberately engaging with a creative and developmental approach I was craving. Conducting the thesis work on top of finishing all the other fourth year courses and working part time as a waitress was punishing[3]. I resolved never to do research again[4].

I adored those child drawings, their stick figured innocence, their genius beauty. After graduating, I pivoted my sights to art school and began to piece together a portfolio for submission. Waitressing, I couldn’t afford to apply to more than one school[5]. I chose Emily Carr. There, portfolio submissions required works using three different mediums exploring an artist chosen theme AND encased within a container constructed by the artist that expanded, or at least aligned, on that theme. Shipment costs, of course, were the responsibility of the artist. Why am I recalling these stories? Hindsight explorations. For the constructed container, the most challenging aspect of the portfolio package, I chose to create…wait for it…a liquor store box-sized ceramic eyeball.

At the time I was working with a friend’s mum in her pottery studio, and I explained my approach and plan for the eyeball—it would be two separate ovals (bowls), constructed using clay slabs with holes on the sides near the lip where I would attach metal hinges and a latch after the two halves were fired. This seemed simple to me, but L. refused, explaining it just wouldn’t work, it couldn’t be done. Looking back, I realise my mistake was using the word ‘eyeball’ – I should have simplified the concept to “two bowls that hinge together” or even, “two oval slab bowls, a top and a bottom”. Full stop on the construction of a container for my portfolio submission. No eyeballs in her kiln. I spent that summer trying to puzzle other ways to make a large eyeball that would hold multiple pieces of art. I couldn’t figure it out. And the portfolio gathered dust. I laugh now, wondering why I didn’t consider a different object, a different container (even the liquor store box would have done the trick!). But I (eye) didn’t. And that same summer I met the man who would become my husband and I shelved the idea (eye-dea) of art school[6].

Its’s twenty-eight years later and it’s only now I’m learning to really see. And I recognise a wilful blindness with my writing too. I’ve returned to working on what I call my “long form project”[7]. I have years of writing around the same themes, writing that I have refused to re-read or explore for fear of what I will discover there, what I didn’t want to see. To raise the girls the way I wanted them to experience “family” I kept myself blind[8].

This post is too long. This month has been wretched[9]. I decided to print out the pieces I’ve written as part of the long form project, “to see” the extent of material I have. I was stunned to discover it’s 208 pages, 74, 385 words long. This doesn’t include more recent writings towards this project, nor does it include parts written into ten plus years of notebook writing. Initially, I felt proudly amazed I have so much material to work with…then I spiralled …I can’t see where it’s going, how to piece it together…I am floating blind again. Still.

But …I will read what I have written, use my hindsight and my insight, my nascent ability to see the layers and sift the meanings from my own words. I know I have returned to a path of art, following a decades long detour. I wish it was not so painful.

[1] Blue Salamander, a symbol of moving between worlds, transitions and an ability to regenerate, went to the incredibly generous couple who gifted me their riverside house for the winter after I left my marriage. A friend coined it The Glass Chalet. The couple joke, calling their place a home for wayward women. I am not their first.

[2] Razing? This is exactly what I have done by choosing a life of independence…what I have committed through decommitment.

[3] Because my prof was new to the department, he pushed the project to a level worthy of publication, research far beyond the expectations for an undergrad. I fought with the departmental panel, assuring them I could complete the work. The panel pushed back, insisting it was PhD level, too much even for a Masters student. I ended up presenting eleven iterations of my research proposal to the departmental panel before getting the go ahead for ethics submission and beginning the project.

[4] Ha ha …the universe has a sense of humour doesn’t it? Research features heavy in much of my professional career. Interestingly, when I doodle in my work notes during meetings, I have always drawn…eyeballs.

[5] I made $4.25 an hour.

[6] Later that summer, L. rushed into the lobby of the restaurant during one of my shifts, her hair a zany mess and her arms waving the air with her eureka moment. She shouted at me over the din of the restaurant in full summer swing: “I know how you can do it! It will work!!!”. I’ll never forget her despondency when I explained I’d met a man, that I wouldn’t be going to art school. I was 23, the same age my eldest daughter is now. This horrifies me. Maybe it shouldn’t. But it does.

[7] When I referred to a “long form project” during a recent online writing session, one woman pressed me to define my project more specifically. Was it a memoir? It must be a memoir. No, I explained, it’s creative non-fiction, collage work, a series of vignettes, but along various narrative throughlines (four), and the vignettes are kind of veering into fiction. It’s a memoir she repeated, then went on to explain she’d just finished her PhD in literary criticism. Well, that explains it, I thought, but didn’t say anything more. Days later, when I was doing the dishes, I came up with the right category for my work: it’s a memoir with wings. Stick that up your store bookshelf.

[8] This is incredibly hard to write here, to admit. I suspect my self-suppression, the shame in that, is what my long form project explores…I don’t know. I feel lost. Untethered.

[9] My mum suffered two falls, one where I needed to take her shockingly bruised body to the hospital for a wrist x-ray (not broken); my ex-husband (first time calling him this) is dating …I am told about the women through our children, pasting an expression of impassiveness to my face to offer the support they need to process this news (I make myself beige); I’m fielding daily tear-filled calls from my eldest daughter who broke off with her partner of three years…both of us cry on the phone…I try to be the strong and supportive mum I need to be…I fail; I visit my father in his subsidized housing apartment, taking any leftover protein from my own meals because I know he sustains himself on honeynut cheerios; his interest in the world is fast dissolving, his memory, like my mother’s, with it; I long for the sounds of spring peepers, chorus frogs and wood frogs I no longer hear living in the city, and I weep about the loss of the garden; I refuse to attend to world news because I know it will break me; I float through my workdays, convincing my colleagues I am indeed a senior policy advisor, I’m amazed by my own performance; I have separated the muse from the man, the divine from the human, a painful yet necessary separation, for how else to cultivate different ways of knowing, practice other ways of seeing?