We start, this time, at an art opening at a local gallery. It’s a month after I walked out of a twenty-seven-year relationship, a twenty-five-year marriage. The clothes I’m wearing hang from the bones of my shoulders and hips cause I’m a walking coat hanger; all the crying seems to have displaced my need to eat. A first. My eyes are sore swollen and pink veined and the skin at my nostrils is red raw. I look like the grim reaper, hollowed out, dark hooded, hawk-eyed and awkward at a culture appreciation event. I’m trying not to look like I spend my days sobbing. I’ve discovered it’s possible to cry and work at the same time; it’s possible to cry and grocery shop at the same time; it’s possible to lift weights at the gym and cry at the same time. I wake with wet cheeks. Every day I wonder when the crying will stop. I don’t know it at the time but daily weeping ends after ten months. After that, sorrow surprises, gushing at inopportune times: online meetings, phone calls, paying at parking meters. Once the sluice gates swing from my eyeballs it’s hard to know how long the tears will flow …minutes maybe…a few hours…a couple weeks. I get good at convincing my colleagues, my friends, my daughters to gloss the crying, it’s normal, nothing to worry about, this river of grief flowing through. I cry and continue to be “productive”. I cry but with wider spans of time between jags.

The art opening. There are many people crowding the gallery space, but when I enter, I lock eyes with a woman across the room. I think: I know that woman… I move toward the nearest wall and gaze at the paintings there, round the perimeter, trying to focus on the art but I can feel the woman’s eyes warming my back. Who is she? I’m three-quarters round the gallery when I realise it’s H, my (ex) husband’s first wife.

I’d met H only twice, both times at funerals, where we’d shook hands and exchanged expressions of…puzzled bewilderment.

By the fourth wall of my self-guided gallery tour I make up my mind to speak to her, introduce myself. And when I turn around, she’s directly behind me so I reach to shake her hand saying, You’re H, I’m …

Suzanne, I know.

Welcome to the club of ex-wives! I blurt, laughing, grasping her hand.

Her eyes widen, not quite believing. No! she gasps. She says, I can’t believe you lasted as long as you did! Then she says, Are you a hugging person?

We hug for a long time. It feels like there’s only the two of us in the gallery, in the whole wide world, though a joyfully noisy crowd and beautiful art works orbit us.

Why the memories of H today? What has this to do with creative writing? Well, a few weeks ago, I went to watch H perform in a play. She played the lead role in W;t, a one act play written by Margaret Edson. H’s performance was so good, marvellous really. It’s an exceedingly challenging role due to the linguistic and conceptual gymnastics of so many of its lines. I was delighted by H’s accomplishment, the whole performance as well as the playwriting and the emotional impact of it all. Sitting there, in the theatre audience dark, I played participant within a work of art in a way that enabled me to understand my own long project writings in a new way. I’ll try to articulate this.

The play, W;t, combines several different components:

- A story line: a strong, independent, professional academic woman’s career is overcome because she is dying of cancer

- A weaving of disparate academic elements, using dialogue, to elevate one of the play’s overall meanings (there are a few) about what might be lost by devoting one’s life focus toward intellectual advancement at the expense of living, experiencing joy: language, lingo, and theory from medical research (oncology) right up alongside/interspersed with literary criticism (metaphysical poet John Donne)

- Scenes from a variety of time periods with clear signals to guide the audience: the scenes do not progress in chronological order, instead, the sequencing jumps forward and backward in time and uses lighting, stage positioning, stage props, gesture and language variations to signal to the audience where and when the scene is taking place (e.g., a hospital, a lecture hall, a living room in a childhood home, etc.)

- A main character narrator who forces audience participation and explicitly speaks about the structure of the play: the “fourth wall” is broken several times throughout the play when the main character addresses the audience directly, calling out into the dark and reacting as the audience reacts, but also, explaining how the play is put together and giving away the ending (death) at the beginning with the opening lines.

- Other components…but I’m drifting too far from my point so, let’s refocus…

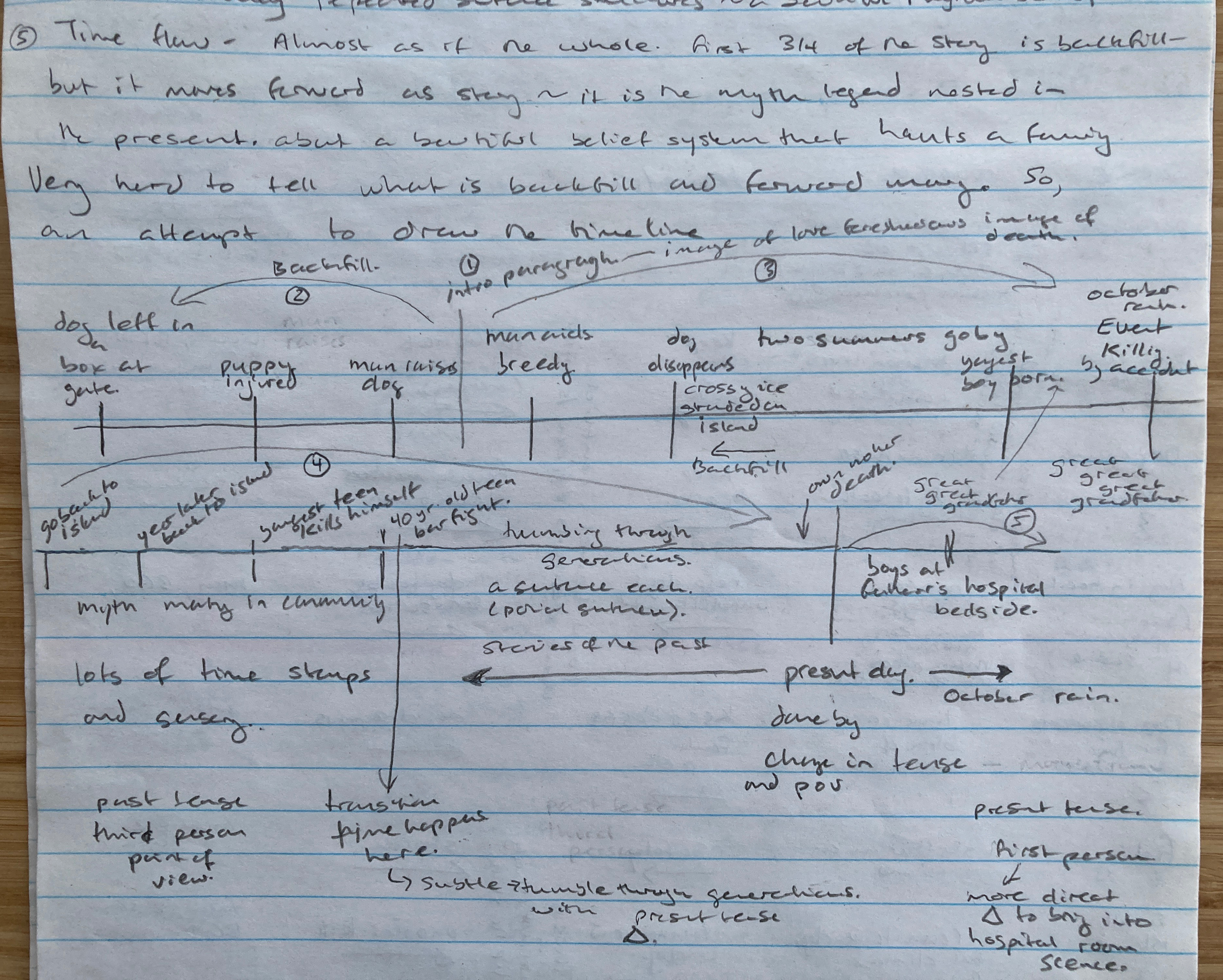

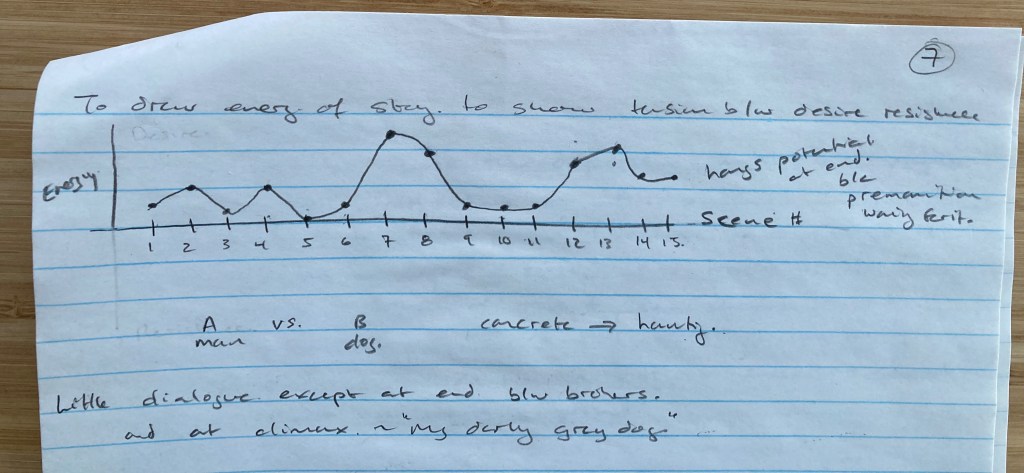

Watching how all these components came together on the stage helped me to see how my own long project (book length) writing is also made up of quite a few different components, so I decided to list them[1]:

- A main story line: a woman’s desire to create a “perfect family” is thwarted

- A weaving of pop cultural elements (movie lines, mostly from 1980s movies) to provide comic relief but also to elevate one of the story’s overall meanings about how we are silenced through shame, both interpersonally and culturally. Too complicated to explain here, but the technique applies the use of humour and language layering as a coping mechanism for characters in emotional pain. Like a play, this is predominantly done through dialogue.

- Scenes from a variety of time periods associated with the protagonist/narrator (yes, I think these are the same character at this point, a persona of yours truly [insert graceful sweeping bow]). The “digression” elements of the overall structure (will touch on this below) are stories during the narrator’s childhood and during the narrator’s prehistory (before the protagonist is born) and some scenes are forward in time from the main story arc. I know, this is confusing to read in the abstract …in my mind it works though. What I continue to try to figure out is what I will use as the “signals” for the reader to keep track of where and when they are in the story. I don’t want this to be a disorienting mess…the path must be clear and effortless for a reader to follow[2].

- I really like the use of second person point of view brought into the experience of reading. I’m sure you’ve noticed how frequently I speak to you directly through my writings. It makes me feel less alone. Gives me a sense that I’m being supported and nurtured and held and connecting through gossamer threads winding the world wide web. I like the collusion feel of it. It’s an intimacy. In the long project, I feel it’s a way to pull disparate elements of the writing together…a way for the narrator to admit she’s figuring things out as she goes and she’s making mistakes and maybe even this is one of them…trying to put pieces of this long project together before great swaths of it have even been drafted. Am I being too deterministic with my project by building out this recipe? You might let me know.

- Another element I’m playing with is the integration of scientific research (neurophysiological development, epigenetics, trauma theory, attachment theory, blah blah)…but NOT from a pedantic standpoint[3]…I’m trying to sprinkle these in creatively playing with narrative distance, micro and macro settings, and personification as the formal techniques to make it artistic, even beautiful. Very much in development.

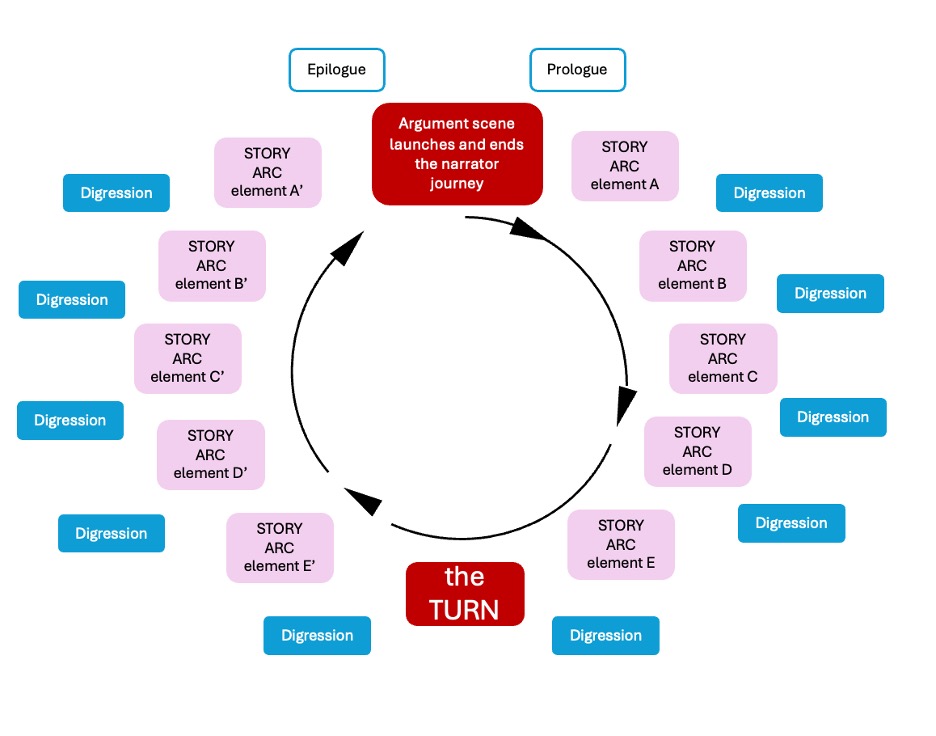

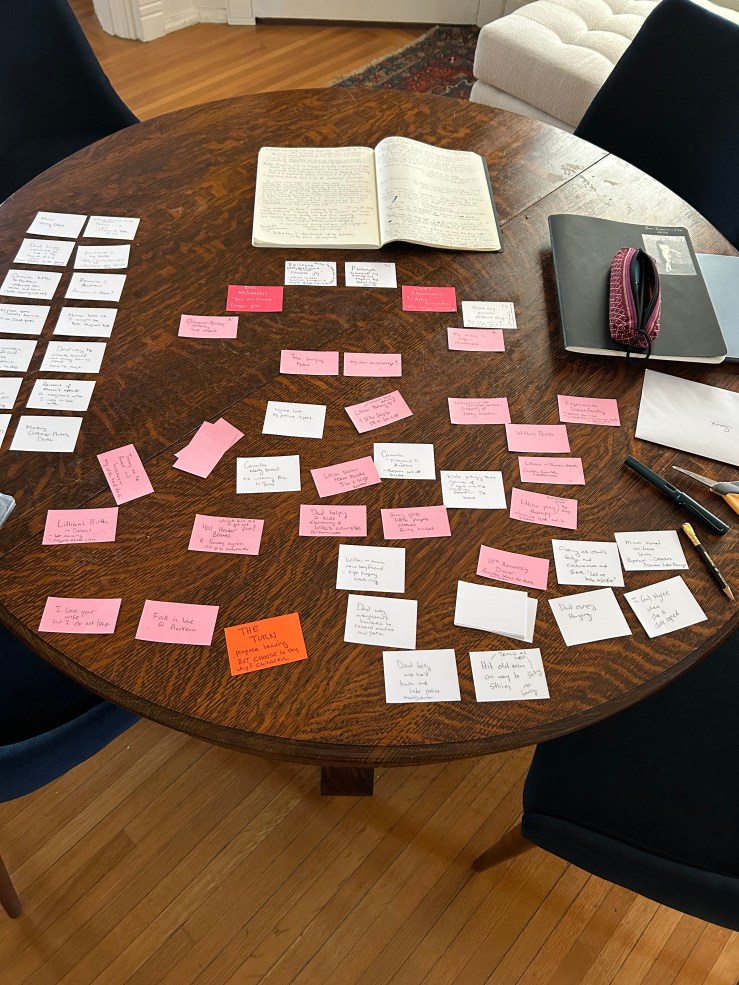

I wrote last month about coming to the idea of applying a ring structure for my long project. I’ve continued to play with piecing of story elements using different coloured cards and writing, well, not quite scene titles, I guess they’re event titles, on little cards. This way, I can move the events around and play with the various sequencing of information a reader will read from the beginning of a book to its end. I’m still figuring this out…a lot of the story events have been written, albeit in very (very!) drafty bits…some of them have yet to be written. Here’s simplified diagram of the ring structure I’m working toward, the model, followed by a photo of this exercise in progress.

Working this way, I’ve come to realise the story, and what it is I want to say through its writing, will be served better by fictionalizing it. This is a VERY BIG change[4]. Until now, I’ve been working with nonfiction, adhering to “what really happened” and some sort of “truth” from my own experiences of events. But it’s clear, especially if trying to match structural elements of the main story line so they hang in mirror image to one another to be “felt/intuited” by a reader, taking off into imagination territory will enable me to explore and uphold story and story meaning more comprehensively than sticking to the facts.

So. All these elements, it’s kind of like a recipe no? It’s like I’m assembling all the story ingredients together to create a book shaped dish. Let’s call it a meal because I want whatever comes out of this process to be satisfyingly delicious…in the, um, read way (I’ve lost the metaphor here but whatevs). I want the writing and reading to be shared pleasure. Mise en place (hit that link, it’s funny) is a French culinary term for having all your recipe ingredients fully prepared before you begin to cook: onions chopped, garlic minced, cans opened, oils and spices measured out. The techniques of cooking…the tools, the timing, the temperature, the equipment…remains equally important…the mise is only one phase of the cooking. In this way, I’m confident that setting all these components out on my metaphorical countertop is not deterministic, but simply a “recipe” for helping me to contain the associative creative writings towards realising this project. A cure for chaos, so to speak. Or layering different melodies into harmony so they play in concert together.

[1] A caveat: these elements are fluid, not locked down…this is how they emerge at the moment of current drafting; I’m open to shifts and changes…I’m learning about what my writing is about as I write it…there’s no other way through it …I’m remaining flexible.

[2] The signals could be comprised of a repeated image or repeated paragraph elements or a phrase or even a super-duper clear signpost from the narrator “and now we are back in [insert location element]”. I have a particularly arresting image in this work (a fetus in a jar)—an aside, I was delighted to discover John Irving includes the same image in Hotel New Hampshire—but I know, from having included this image in writings I have workshopped, how heavily it lands with people (and often, not well)…so I’m looking for something less overt. The fetus in a jar will of course be part of the story…but it speaks volumes as itself and doesn’t require any additional window dressing emphasis.

[3] I have made this mistake many many many times…I can spot it now, when I write this way…I’m practicing transforming it.

[4] Have to say, I’m frightened by this change. Like, what if I can’t do it? Like, what if my imagination is bust? But then I think…well, fuck, what else might I be doing with my time…at least I can try. This is the same attitude I’ve been wrestling with (inner critic can be pretty vocal on this point] about the long project and this incredibly convoluted and complex approach to writing a novel. I mean, I KNOW I could write a decent enough (sufficient for publication? Not sure) essay collection on these topics that would be far easier to complete…but, for some reason, I’m choosing this crazy path …maybe just to see if I can do it. And again, the refrain, Well, fuck, what else might I be doing with my time? This works. I like doing this with my time.