‘I suffer as always from the fear of putting down the first line. It is amazing the terrors, the magics, the prayers, the straightening shyness that assails one’

John Steinbeck, Journal of a Novel: The East of Eden Letters

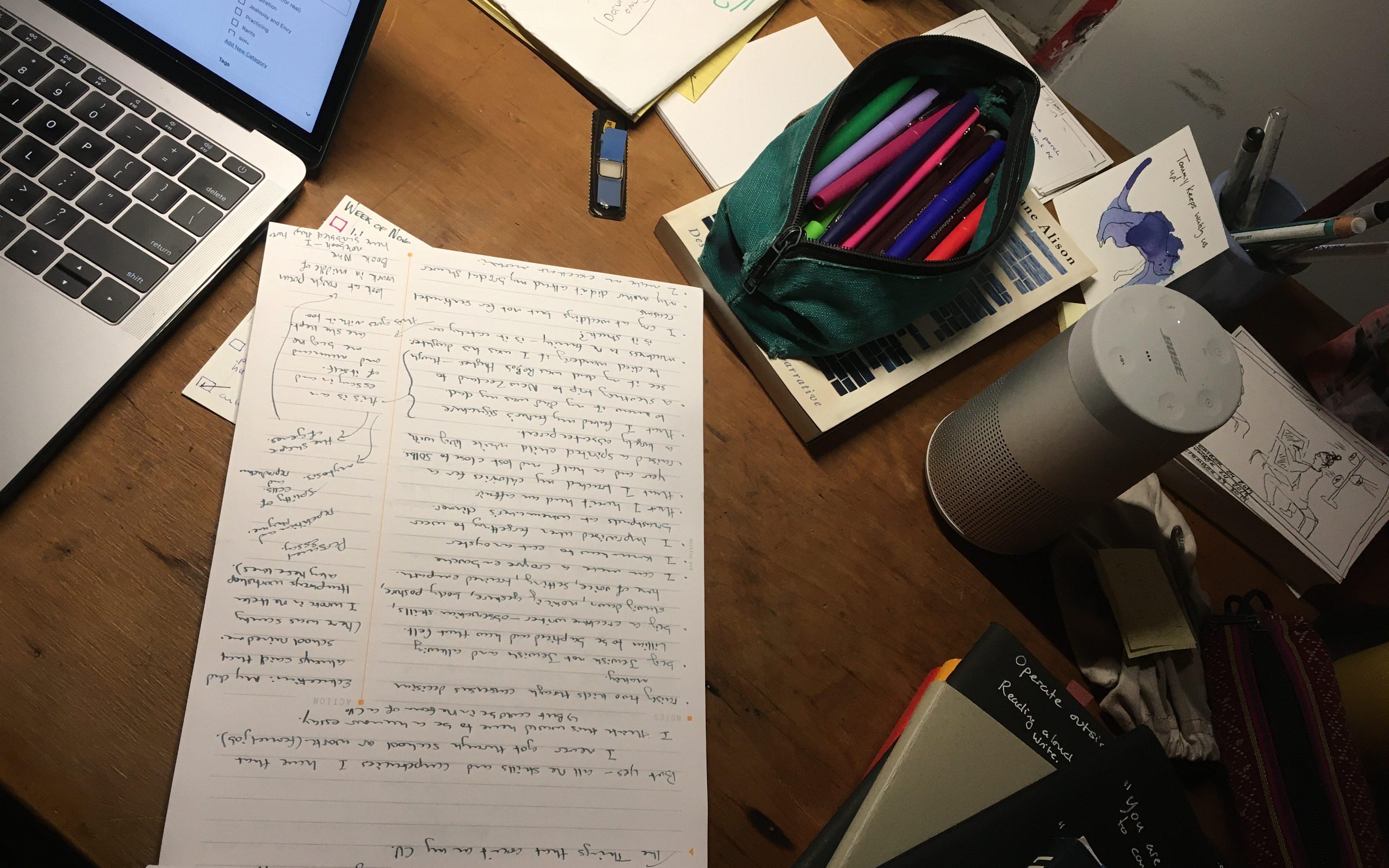

I’ve returned from a week and a half vacation in B.C. Of course, I brought my notebooks, my computer, and some select drawing materials, believing I would have the much needed down time in order to create or work on expanding the draft of a short story I’m working on. That didn’t happen. The time change—even moving as little as three hours towards the sunsets—made me feel nauseous and exhausted. Wonderful visits with family and friends filled the days. The artistic practice routine I’ve guarded and carved at home, dissolved. I let it. Instead, I welcomed the laughter, delicious food and wine, the spectacular mountain views. It’s all essential.

Two weeks not practicing makes it hard to face a blank page. Like any exercise, I need to build back my muscles. Habits help. I’d be dishonest if I didn’t admit the tailspin of self-doubt and anxiety (again?! still?!) about my artistic abilities or my lack of productivity. It’s a comfort knowing most artists feel this way. Most creatives? And then, I wondered, why?

I attended a lecture at Queen’s University this week, a PhD student in the education department exploring how the concept of “creativity” is incorporated and has influenced the Ontario curriculum since the 1880s to now (no small feat) (1). His research demonstrated the word “creative” doesn’t enter common usage until the 1950s or so, an etymological fact that surprised me. The original use of the word, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, and a theological reference the student managed to track down, deviates from the modern definition we bandy about and follows an interesting progression through the next few hundred years.

In the 1640s, creativity was associated with “creationism” and the divine (read: God) ability to make all things, all of “creation”. This older concept of creativity became associated with the idea of a “God – given gift” and that association then became linked with “genius” and “ingenuity”. Read: reserved only for the special, “chosen”, few (and, historically, almost exclusively white males in Europe). Genius was reserved for those bestowed (by God) with the creative power and understood to be an innate gift, not something one might learn (through practice, for example). The tiny tinsel ring of recognition bells might be ringing in your mind….

From there, the concept of creativity grew and changed. But slowly. It wasn’t until the later 1800s that it slipped under a conceptual definition that was more inclusive, through the founding father of kindergarten, Fridrich Froebel, a German educator. He believed all humans are creative (not just geniuses) and ought to be left and encouraged, through play and exploration, to cultivate individual creativity. This seems closer to what we aspire to (and believe?) these days, but artists are still assaulted by imposter syndrome and fear…what happened?

Froebel’s ideas managed to influence curriculum development and implementation as far from Germany as Ontario, but in the early 1900s, it was believed too free and difficult to control alongside more traditional approaches to education. Two world wars with Germany on the opposite side did the conceptual definition no favours. It fell to the wayside. I wonder if it is any coincidence the surrealism, expressionism, cubist and art deco movements grew out of this time, following on the heels of impressionism? Did those artists as children attend kindergartens where they were free to explore their creativity?

J. P. Guilford, a psychologist, peppered his learning theories with “creativity” and the word took hold, sticking through a common usage from the 1950s onwards. Guilford’s conceptual definition broke creativity into component parts: as a problem that could be solved. In this way, creativity was recognized as a set of skills that might be taught. By the 1980s, curriculum had teased art making, “creating”, into a progression of increasingly complex building blocks (and why, perhaps, creative making is widely encouraged in primary schools, and then subtly, through omission, discouraged in secondary schools in favour of learning that supports social efficiency skills (those that will get you a job). This is my era of formative schooling and it makes me question whether my dogged pursuit of “learning to write” by searching and reading so many (too many) books on writing (instead of just getting down to the paper and practicing and exploring more freely, in the Froebel manner) is hindering my progress. I think it is.

More recently, the concept of creativity has embraced and shifted into the idea of creativity as social power: through creativity we are able to reform or revolutionize the world. I don’t know about you, but I feel an intense pressure to use my art toward the greater good. The pressure is immense. It can be, and has been, paralyzing.

The variety of conceptual legacies continue to percolate and bubble our modern sociocultural beliefs about what the definition of “creativity” is. Presently, we draw and squeeze together all five ideas. By looking backwards, following this etymological roller coaster, I’m beginning to understand the lenses I allow to cloud my artistic practice. If knowledge is power, then at least I can face the blank page with a little less reservation.

(1) Trevor Strong