My favourite professor in undergrad taught neurophysiology, biological psychology and behavioural neuroscience of motivation. I have a distinct memory of his explaining how the size of the human brain is governed by the restricted size of the birth canal (technically, it’s referred to as the obstetrical dilemma) . Surprise, turns out it’s a little more complicated than that. Much neurodevelopment continues during the postnatal period and neuroplasticity is lifelong. But beyond this, our brains sufficiently evolved to invent machines with super-fast processing speeds and computational abilities. At this point, most of us have adopted palm-sized prosthetic brains in the form of cell phones, and with them, we have access to more information we could filter, sort or ever hope to synthesize, especially across diverse subjects.

This is what I was thinking about last week when I attended a webinar providing an overview of Google’s Notebook LM, a new AI application launched in December 2023, that basically functions as a virtual research assistant. Let’s call it an(other) extra brain [1].

Yes, I’ll be one of the early adopters, especially for my day job. But I’m also interested in how the technology could become a tool to support creative process. Though, to be sure, a tool used with caution.

A swift summary: LM stands for language model and the application uses the conversational question functionalities of ChatGPT, BUT allows you to curate a discrete library of your own source documents for the AI to search through. So, any question you ask will draw an answer from ONLY the documents you have provided, personalizing sources to a particular project, erecting a knowledge barrier you can control and thus greatly reducing inaccuracies and hallucinations [2].

The application currently integrates Docs, PDFs, txt, and pasted text using the cut and paste function. There’s promise websites will be able to be imported soon. Likely, the import of images, PowerPoint and even Excel sheets will be functional in the not-so-distant future.

I often use the search and find function in documents to locate phrases and key words. This is especially important when reviewing legislation and evidence reports under tight timelines, but I also use the function in creative writing to locate word repetitions, check misplaced homonyms, homophones, homographs, get rid of weasel words [3] etc. But this function has only been possible in one document at a time. I’ve used qualitative analysis software to support analyses and syntheses across interview and focus group transcripts, as well as multiple word documents. Using qualitative software, a considerable amount of time (time in which your brain actually feels like it’s turning to mush) is used to manually “tag” words and phrases in every source transcript or document to a category in order to code the text data. This can take weeks or even months, depending on how much text makes up the project and the theoretical approach you have chosen to apply. Once all of the text data is coded, THEN you can go in and query the dataset for analysis using your coding structure. The capabilities promised by Notebook LM will (almost) eliminate the coding step, allowing a researcher to jump right into querying the data for patterns and moving forward from a super advanced starting line.

Imagine this application for:

- summarizing systematic research reviews (practically this is very similar to conducting qualitative analysis)

- understanding legislation changes over time or creating a bylaws database that could be posted to municipal websites to support citizen Q & A

- referencing medical symptoms and best practice guidelines – could this replace a visit to a family physician, linking a person directly to a pharmacist or triaging a health issue to an allied health care worker for virtual assessment and confirmation, at least for common non-emergency ailments?

- Discovering patterns across historical documents or novels or essays or groups of poems or across all these different types of documents

- Bringing disparate subjects together to spark different ideas, say climate resilience strategies, poetry, child development, hip hop song lyrics and how long to cook an egg [4].

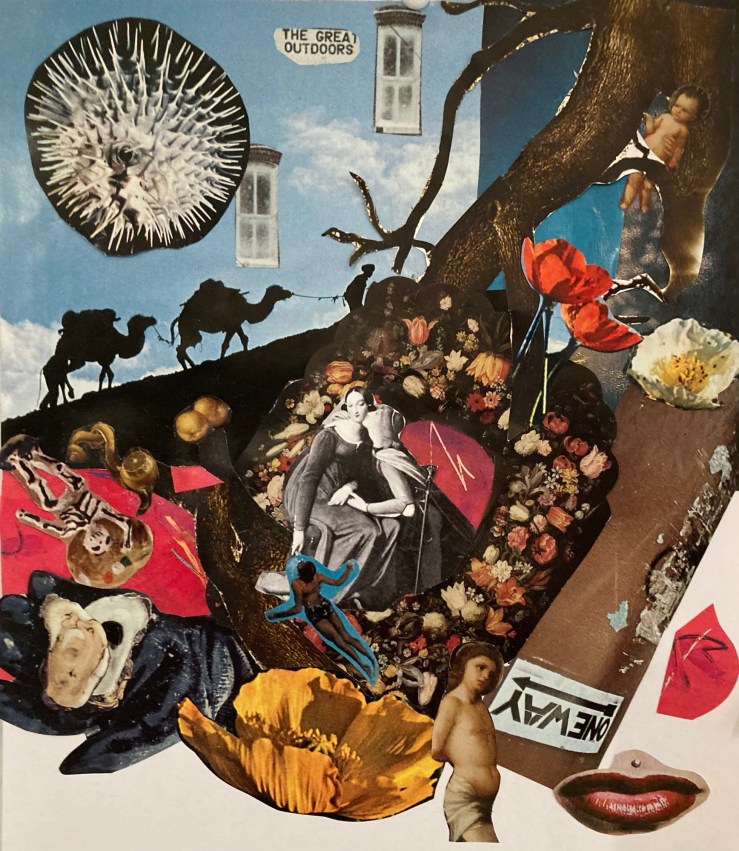

The collage at the top of this post is a good analogy for the possible repercussions Notebook LM threatens related to creative licensing and copyright. I pasted the collage together from bits of cut out magazines and art books as part of a fantastic afternoon workshop facilitated by hiba ali, The Studio x Open Secret: Activating Dreamscapes. The images I used came from artists’ works and photographs from books and National Geographic magazines and I’ve cut and reassembled them without any credit to create my own artwork. Where should the line of creative appropriation, cultural appropriation, or plagiarism be drawn in these new digital spaces and the “new” creative works produced using these tools? [5]

Attending this collage workshop in the same week as the webinar kind of blew my mind – an ocean of virtual playgrounds to swim in. It’s also a little frightening, the control to create frames of knowledge that might hold sway an illusion of authority for many. I’m (somewhat) comforted to learn (also this week! my goodness) the word set boasts a Guinness World Record with the most senses of meaning (430!) of any other word. Other sources award this honour to run with more than 600 senses. Perhaps the english language will retain sufficient nuance an AI might never master (wishful thinking). BUT, language combined with gesture, intonation, facial expression, raw instinct etc. may give AI a run for its money (I hope).

Once we created our collages in the art workshop, we uploaded them to a digital art exhibition “world” space where we co-created together and were able to manipulate the images, integrate a variety of additional media (sound, text, links, gifs etc.). This application is New Art City. It reminds me of the game Minecraft my kids used to play when they were younger. Here’s a link to what I created playing [6] in the New Art City application with my own collage and the virtual gallery space: https://newart.city/show/souxs-virtual-creative-space-space-1.

All this virtual creativity at your fingertips for a song. To be sure, what we create as our real world is built from layers of many worlds—perceptual, spiritual, cultural, relational, linguistic, so many others—and, of course, virtual [7]. Jouer le jeu as they say in French, play the game. But the digital space is really an out of body experience; sometimes we might just have to communicate the old-fashioned way, you know, via email or phone or (gasp!) face to face. Especially when virtual platforms are an invitation to experiment interacting multidimensionally. Like I said, you’re welcome.

[1] Sorry Canadian peeps, the experimental version is only available to those living in the US. Canucks are still waiting to test drive the application.

[2] The information returned is less likely to be made up by the machine… hallucinations are complicated, I’m not going to try to explain them.

[3] From Matt Bell’s Substack, No failure, Only Practice, Exercise #14: Hunting Weasel Words.

[4] I know, weird, but you get what I’m suggesting.

[5] I don’t know the answer to this at all but it’s an interesting question and I would value a discussion.

[6] Other applications that I didn’t use but leave here as reference: Photopea, a free online photo editor; Free3D, free three dimensional models; Creative Commons, “an international nonprofit organization dedicated to helping build and sustain a thriving commons of shared knowledge and culture. Together with an extensive member network and multiple partners, we build capacity, we develop practical solutions, and we advocate for better open sharing of knowledge and culture that serves the public interest.”

[7] As long as the power stays on.